Food Desert Unit

Introduction

A food desert is a low-income area that has restrictions on access to high-quality foods. It is typical for food deserts to occur in cities that have foundations in bodegas and corner stores. As an educator in Providence, Rhode Island, this directly impacts my students. In fact, many of them have been identified these establishments as staples in their community to get food.

Unfortunately, food deserts have many effects on the populations in which they reside. This is particularly concerning for developing children who require proper nutrition to thrive. Given that Achievement First is an extended day, proper nutrition is vital to student success. To alleviate this barrier, students have participated in a Food Desert Unit with a nutritionist from the University of Rhode Island and community activists.

Food Deserts - Teacher Research

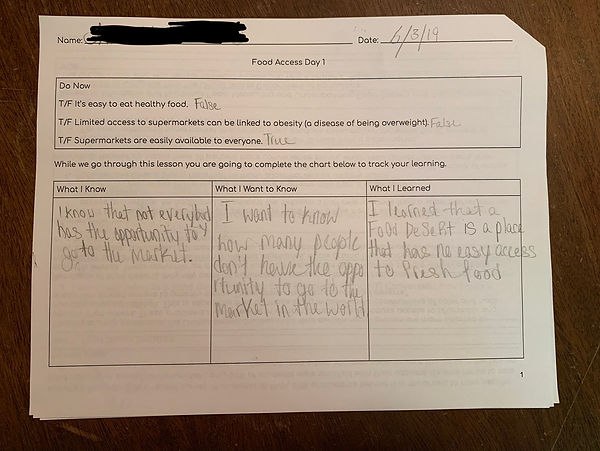

In order to create this experience with my students, I utilized data from a Needs Assessment which illuminated that students believed healthy foods were important yet not easily accessible - particularly within the school. Student data is captured in the images below.

With this data, I sought to learn more about food access and resources in Providence, Rhode Island. My research began with finding lessons on food deserts. The first image below is a lesson from Teaching Tolerance that provided multiple resources such as activities, governmental websites to collect data, and essential questions to focus instruction. One particular resource - seen in the second image below - that became a focal point of my research was the Food Access Research Atlas which would allow students to identify and analyze their specific community. This would later become a large component of our lesson.

After exploring the Food Access Research Atlas, I began to fo us my research on the Providence Community. In a quick Google search (Image 1), I learned about the SNAP - Food Access Project, which helps the elderly, disabled, and homeless people get five prepared meals a week from Subway. This type of community support was inspiring and made me more curious about programs for youth. After continued research, I found Noereem Mena, a Ph.D. student at the University of Rhode Island who specializes in Food Access, Metabolism, and Child nutrition (Image 2). Immediately I contacted her to see if she would be a guest speaker.

From this data and research, I was able to identify a topic for access. Studying food deserts allows students to explore society, health education, potential career pathways, and evaluate their own community. Given its relevance and opportunity, I created a short unit plan which encompassed a number of activities for students to engage with while exploring food deserts. Students began by creating a map of their neighborhood using a coordinate grid. This activity was a smooth transition from our last unit in mathematics and brought a real-world application to our learning that students enjoyed. It also allowed them to begin evaluating which types of food stores were within their community. From here, students had explicit instruction of food deserts and interacted with Noereem Mena, a PhD student at the University of Rhode Island.

Preparing for the Lesson

Our last unit in mathematics developed student's geometrical understanding and explicitly introduced them to a coordinate grid. As a culminating project and segway into our food desert mini-lesson, students completed a Map Your Neighborhood Project. For this activity, students practiced plotting coordinate pairs as well as identify8ing coordinate pairs. Students then identified key locations in their own neighborhood and created a map. Without naming it, students were set up to already evaluate food access in their own community. The pictures below demonstrate my students' final projects.

This piece of student work demonstrates how one student was able to identify different types of food stores in her neighborhood. By identifying Stop & Shop as a place, her mom buys food she is suggesting that this is where the food for family meals comes from while the corner store where she gets her sweets is a different agenda.

This piece of student work demonstrates how one student was able to identify different types of food stores in her neighborhood. Specifically, she was able to identify the cultural relevance of food stores in her community. This illuminates an important piece of food access that would later be used in our conversations.

Engaging in the Lesson

This project prepared students to engage in an introduction lesson on food deserts. My explicit instruction allowed students to watch a video from a 70-year-old woman living in a food desert in Washington D.C, create their own understanding of the word food desert, and evaluate their own neighborhoods.

Throughout the lesson students used KWL charts to capture their learning. In this piece of evidence, the students are able to articulate that a food desert is a place where people do not have easy access to fresh food. Many students gained a deeper insight into the topic after watching the video below. From this video, students were able to identify the three components of a food desert: (1) low-income community, (2) less than 0.5 miles from a grocery store, and (3) no vehicle.

In this piece of evidence, students identified a supermarket, convenience store, and fast food restaurant in their community to analysis whether their own community was a food desert. Many students were able to identify the discrepancy in prices from one place to another which allowed them to make a connection between food deserts, poverty, and obesity.

Guest Speaker

To make this mini-unit more tangible, I invited a guest speaker to my classroom to speak about the impact of food deserts, the work being done in their own community, and how students can practice their own advocacy. As an alumnus of the Univerity of Rhode Island, I was able to connect with Noereem Mena, a Ph.D. student in Nutrition and Dietetics. At URI, Noereem has held the position of Lead Lab Manager for Food Access, Metabolism, and Child Nutrition. After connecting with her via phone, we were able to set a date for her to come speak with my students. Once this was set, I sent an email to inform her of our learning and confirm logistics.

An additional step of preparation for our guest speaker was to create questions. While Noereem and myself encouraged students to ask questions, I created questions for students to ask if they needed support. At the beginning of the presentation, students used the questions pictured below to start a conversation that later led to more organic questions. From these conversations, students were able to ask further questions about holistic healthy lifestyles, mental health, and obesity.

Seen in the image below is students engagement with guest speaker Noereem Mena. Although students were hesitant at first after a few moments sutdents began asking many authentic questions. Students wondered about dieting, obesity, and how food access related to sports performance.

Reflection

Student reflections after completion of the mini-unit on food deserts and presentation from a guest speaker are captured below:

-

"Noereem shared with us that "Being a voice for my community was the greatest blessing" while studying at the University of Rhode Island and I want to be like her and serve my community. Although I'm not sure about healthy foods because I like Takis a lot, maybe I will be a researcher when I grow up." - PMA Student

-

"I never really thought about the food in my neighborhood and how it could impact me until this project. Noereem told us we could get lunches in the park over the summer which sounded really cool." -PMA Student

Conclusion

After analyzing the results of a Needs Survey, it was apparent to me that my students were seeking more. After multiple informal conversations, I was able to identify gaps in my students understanding about nutrition and nutritional programs offered in their community. Numerous pieces of research led me to resources both nationally and within the state to educate my students on. Most notably was the experience to explore their won community, assess their own community, and learn from a professional in the field of nutrition. Students learned the definition and criteria of a food desert, if they lived in a food desert themselves, programs of support in their community, and a new career option.